-

Meet J.E.B. Mungall

J.E.B. Mungall I have been a teacher of English Literature and Literacy for over a decade, serving in inner city schools, and presently remotely online. Now, I’m a self-published author, having written a fantasy novel: Antiphon: Fire and Stone, a children’s book, The Legend of Tam Lin, and am working on a new non-fiction book about teaching English Language Arts in the world of Artificial Intelligence.

I earned my degree in English with a concentration in Creative Writing from Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge, LA where I currently reside with my wife and three children. I have long been passionate about language, linguistics, and literature–in other words, I’m all about the stories we tell, how we tell them, and why they’re so important. Storytelling (whether true or fiction) has been the mode by which humanity has shared its most important truths about themselves, Creation, and the Divine. So if you ever ask yourself “why is my English class important?” That’ll be why. It doesn’t matter if you’re interested in metaphysics, video games, mathematics, carpentry, welding, or professional wrestling. Everything hinges on the telling of the story.

-

A Better Way to Teach Writing in the Age of AI

Process-Based Checkpoints That Work

Let’s be honest: the writing landscape has changed. AI tools like ChatGPT aren’t just looming on the horizon—they’re already in your students’ browsers.

And while some educators are still scrambling for the perfect AI detector (spoiler: it doesn’t exist), others are asking a better question:

How do we teach writing in a world where students can outsource the whole thing?

The answer? Go back to something that’s always worked—but with a few smart updates.

🔁 The Checkpoint Writing Model

Instead of policing the final draft, start engaging students throughout the writing process. Here’s a structure I’ve used in my classroom (and it’s fully adaptable for middle school, high school, or college instruction):

✅ Checkpoint 1: Brainstorming or Topic Proposal

Students generate ideas (with or without AI help), but must also explain their thinking. If they use an AI prompt, they submit both the AI response and a 2–3 sentence summary of what inspired them.

Bonus: This gives you an early read on their voice and originality.

✅ Checkpoint 2: Outline or Planning Page

Before drafting, students submit a basic outline or mind map. You can provide a template or let them use AI to help structure their argument—but again, they have to explain what they kept, modified, or rejected.

This stage reinforces organization, voice, and accountability.

✅ Checkpoint 3: First Draft (Ungraded)

This isn’t a final product. It’s a progress check. Use peer review, AI-assisted feedback, or conference check-ins to help them revise—and coach them through improving, not just submitting.

✅ Checkpoint 4: Final Draft + Reflection

Students turn in their final draft with a short written reflection:

- What changed since your outline?

- Did you use any tools or suggestions (AI or otherwise)?

- What are you most proud of?

Why This Works:

✔️ It builds trust and transparency.

✔️ It makes writing more process-focused, not product-obsessed.

✔️ It gives students permission to use AI—but in a way that develops skill, not shortcuts it.

✔️ And most importantly? It helps you sleep at night.

📘 Want more like this?

This is just one of the many real-world strategies I share in my new book,

AI for Good, Not Evil: A Language Arts Teacher’s Handbook.If you’re looking for practical tools, smart prompts, and ethical frameworks for teaching writing with AI—not in spite of it—this book is for you.

👀 Grab a copy here

🎙 Or book a virtual PD for your team

-

Digital Witch Hunts: Academic Dishonesty with AI

Artificial Intelligence is rapidly changing education, but not always for the better. One of the most troubling developments is the reliance on AI detection tools to assess whether students have used AI to complete their assignments. The problem? These tools are often wildly inaccurate, inconsistent, and, ironically, create the very environment they seek to prevent—one where students and educators alike must cater their work to the whims of an unthinking algorithm.

A Real-World Example of AI Detector Failures

Recently, my assistant principal (AP), who is working on another degree, called me for advice after being falsely accused of using AI to write a paper. His professor informed him that their institution’s third-party AI detection software flagged his submission as 68% AI-generated.

The issue? My AP is not only a principled educator but also a talented writer. He knew with certainty that he had not used AI to generate any portion of the paper. What he had done, however, was follow the exemplar report given to the class and had accepted a few grammatical suggestions from Microsoft’s built-in tools—like replacing “in spite of” with “despite.” That was the extent of the so-called “AI generation.”

Out of curiosity, he asked if I could run the same paper through my school’s AI detector. The result? It flagged his paper as only 8% AI-generated. For comparison, the exemplar report from his professor’s institution scored 13% AI-generated—a higher percentage than his own paper!

How is it possible that two separate AI detection tools produced such drastically different results? The answer is simple: these tools are not reliable.

A Flawed Approach to Academic Integrity

Given the discrepancy, the professor had a few options. She chose to allow my AP to resubmit his paper with a 15% penalty, provided that it passed another AI detection scan. He refused. To do so would be an admission of wrongdoing when none had occurred.

Ultimately, since the paper was part of a multi-stage assignment, the professor decided to “let it go,” with the caveat that if future submissions were flagged, further action would be taken.

So, let’s get this straight: the professor was comfortable relying entirely on an AI algorithm to do her job because she suspected a student had used an AI algorithm to do his. The irony is staggering.

The Harmful Effects of AI Detection Overreliance

This situation highlights the growing problem with AI detectors in education:

- They shift the focus away from learning. Instead of focusing on improving his work, my AP is now more concerned about avoiding AI detection flags.

- They encourage poor writing. One way to avoid being flagged is to write less fluently and more mechanically—an absurd incentive in an educational setting.

- They force students to cater their writing to flawed algorithms. If one AI detector flags a paper at 68% AI-generated and another at 8%, which one should students trust? The obvious answer is neither.

What Should Educators Do Instead?

Some suggest comparing flagged assignments to prior student writing samples to verify authenticity. This is a reasonable approach—but it requires effort on the part of the professor. The reality is that as AI-assisted writing becomes more ubiquitous, educators may not have purely student-generated samples for comparison.

Instead of relying solely on flawed AI detection software, educators must rethink how they assess student writing. Some effective strategies include:

- Process-Based Writing Assignments – Requiring drafts, revisions, and in-class writing samples makes it easier to verify authentic student work.

- Oral Defenses & Discussions – Having students verbally explain their arguments can confirm whether they understand their own writing.

- Updated Academic Integrity Policies – Institutions must recognize that AI is here to stay and shift the conversation from detection to ethical use of AI tools.

A Final Thought

The reliance on AI detection tools to catch academic dishonesty is not just impractical—it is counterproductive. These tools lack consistency, produce false positives, and ultimately create an adversarial dynamic between students and educators. If we do not address this issue now, we risk creating a system where students are forced to write not for their professors, but for the approval of an algorithm.

And that is not education.

-

An Introduction to Highland Swordsmanship

Background

I’ve been teaching at the high school level online since 2015 (you know, before COVID made it vogue to do so). But I’d had a taste of it as a student since 2010 with the Cateran Society, where I began learning Highland Broadsword. It involved reading primary and secondary sources on Highland Broadsword fencing, videoing myself and fencing partners performing these, sending them to skilled instructors, and implementing the feedback given, then working toward fencing a competent fencer of another discipline entirely. The method isn’t ideal, but it worked. After writing some online curriculum for my English and Speech courses, I considered that I should perhaps also petition my principal to approve a Highland Broadsword course–sort of a hybrid of history and PE. My then-principal agreed and I was off. I thought I’d use this medium to republish some of the informational/historical portions of that course.

Scottish Highlanders and the British Empire

During the 18th Century, the Highland Scot came into vogue in Great Britain. After years of repression and persecution of the Scottish Gael, it was ironically the Highland Regiments of the British Army that preserved many of the proud Gaelic martial traditions of the Highland Broadsword. In the British Empire, this sword-fighting tradition made its way around the world and was tested by all manner of martial arts: from Europe, to the Americas, to India, China, and Japan.

Highland Broadsword Practiced Today

People the world over have begun to take up the old art of the Highland Broadsword. Through the research and interpretation of old Highland Broadsword manuals written by various broadsword masters in the period, dedicated swordsmen have been able to recreate and resurrect this once prolific and highly effective style of swordsmanship that is as much finesse as it is brutal force. Now, Highland Broadswords are being seen again all over the world. Broadsword Academies can be found in Germany, Finland, Russia, all over the U.S. and Canada, and of course, in Scotland and the U.K.

Singlestick and Cudgeling

Like the Scots of centuries past, practitioners of the Art of the Highland Broadsword continue to use some of the same tried and true methods of practice: one being the use of a wooden singlestick with a leather or wicker basket to protect the hand. This training tool eventually developed into a sport in its own right called “singlestick” or “cudgeling”. This system was even at one time an Olympic event! Though short-lived there, it has seen a great resurgence and is used by not only Scottish, but also English, Irish, and American fencing systems.

Historical European Martial Arts (HEMA)

Historical Scottish fencing is not the only European martial art that has been rediscovered, revived, or relearned from old written sources. There are many different styles of Historical European Martial Arts (HEMA) that have come to light with varying degrees of popularity in recent decades. These range from German and Italian Longsword, English broadsword and smallsword, Irish and French stick-fighting, wrestling styles from all over, French, Spanish, and Italian rapier, Polish saber, and the list goes on and on. Unlike with Eastern Martial Arts, like Kung Fu or Karate, there is not a linear unbroken line of master to apprentice for most of these arts. When reading older sources, sometimes interpretations will need to be made and sometimes scholars and practitioners will disagree with one another.

Closing

Highland Swordsmanship is not only part of a rich and varied combat tradition of Europe, but also part of the tapestry of Scotland’s storied culture, illustrating both the mystique of the Scottish warrior and the narrative of cultural borrowing and transfer from those around it, and also its interplay around the world with those whom the British Empire colonized, battled, and defended prior to the advent of mechanized warfare.

british empire, broadsword, broadsword academy, caledonian, cateran society, claymore, colonial history, colonial period, cudgeling, education, fencing, hema, henry angelo, highlander, historical european martial arts, historical fencing, history, olympic fencing, online education, scotland, scottish, scottish history, single stick, singlestick, swords -

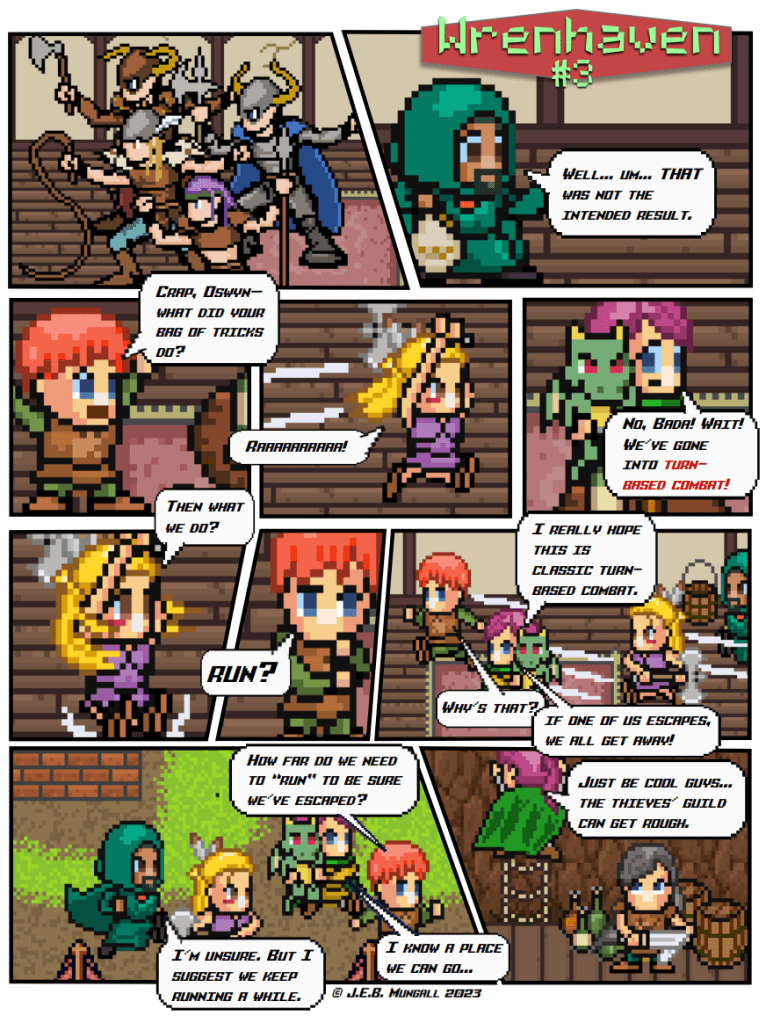

Wrenhaven Webcomic #3

-

Ceding an Arsenal to Your Ideological Opponents: ChatGPT

I’ve been a big proponent of AI-language generation tools like ChatGPT and AI-art generation tools like PhotoLeap. I find myself often at odds with fellow English teachers, authors, and artists in this. They argue that these tools can undermine the creativity, nuance, and originality that are essential to artistic and literary expression. I likewise find myself discussing ChatGPT with more conservative friends, who express concerns about the Left-leaning programming inherent in the AI. They argue that use of the tool is too limited and designed to support Leftist political agendas. However, I think that it’s foolish to cede such a powerful tool to ideological opponents and likewise foolish to pretend that such a tool is going to go away.

English teachers, authors, and artists argue that AI-generated writing or art lacks the emotional depth and human touch that is necessary for truly meaningful work. Others worry that the use of AI language generation tools can lead to a homogenization of language and culture, where all writing and speech sounds the same, and individual expression is lost. Some also express concern that the use of AI-art generation tools can lead to a devaluation of human labor and talent as the creation of art becomes increasingly automated and less reliant on human skill and creativity. These critics caution against relying too heavily on AI-generated content and encourage a continued emphasis on human creativity and expression. I can’t say that these arguments lack merit. Further, the idea that as automation increases, making production-type jobs fewer and fewer, that we will be moved towards more artistic endeavors becomes problematic as AI-created artforms flood the world.

I’ve discussed this at length with other teachers at my school (which is fully remote online school), and there is significant concern about cheating and plagiarism. When I first came to ChatGPT, I spent three weeks in a daze trying to figure out how I could address this in my courses. I could input my detailed prompt for my students’ essay exam on Beowulf and get quite good responses that differed each time I put it in. Gone were the days where I could easily pick out plagiarized work based on certain phrases I’ve seen across multiple papers. But the more I considered it, the more I realized this tool would not be going away, and as good as it is now, the technology will only ever get better. What I should be doing then, is teaching my students how to use the tool responsibly to put their own thoughts and understanding into well-written text rather than just let my students find it and figure it out on their own. To ignore this tool would be a disservice to my students. Does this mean to discourage my students from writing? By no means! In fact, it can actually facilitate writing among students who would otherwise NEVER write any text longer than an email beyond their academic career.

Of course, that ChatGPT facilitates MORE people from sharing their thoughts in a more coherent fashion than ever known in human civilization. This can create a flood of information—which is already an issue with the Internet. But right now, content-creators of various ideological perspectives are widely available. However, if tools like ChatGPT are wholesale eschewed by any prominent political party you run into a number of problems. Conservatives or those of any political ideology should not ignore AI language generating tools like ChatGPT or cede such tools to their ideological opponents because these tools have the potential to shape public discourse and opinion in significant ways. As AI-generators become more sophisticated and widely used, they have the potential to influence public policy, shape public perception, and impact social and political outcomes.

By ignoring or ceding AI language generating tools to their ideological opponents, conservatives risk losing the ability to shape public opinion and influence public policy. As AI language models become more prevalent in the public sphere, they will increasingly shape public perception and discourse, and it is essential for conservatives to engage with these tools in order to ensure that their perspectives and beliefs are represented and considered. Moreover, ignoring or ceding AI language generating tools to their ideological opponents may also reinforce existing biases and echo chambers in public discourse. If only one side of the political spectrum is using AI language generating tools to shape public opinion and discourse, then the perspectives and beliefs of the other side may be excluded or marginalized, leading to an even more polarized and divided public discourse.

-

Wrenhaven Webcomic #2

-

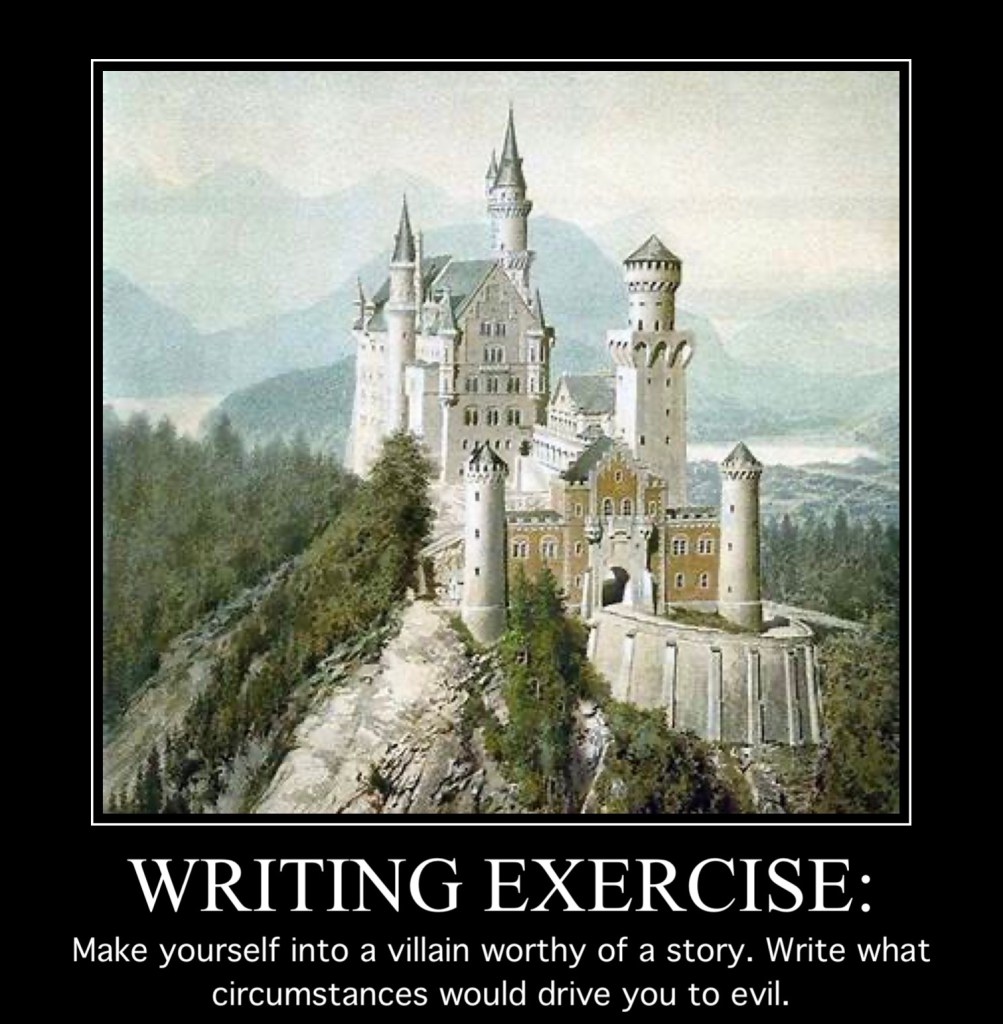

When You’re the Villain in Your Story

I came across a painting someone shared on Facebook that seemed to purposely lack context and was posted with a bit of cheek. I recognized it, though it took me a second to place it. It was one of one of Adolf Hitler’s paintings—which sent me on a bit of a thought train… It’s long been considered how different the world would be had Hitler just been accepted into art school instead of being rejected as he was. When most people see his artwork, they’re surprised to see the works are as good as they are. We of course rightly have a strong negativity bias and so considering that anything even remotely beautiful being expressed out of that mind is hard to fathom—and yet, we have the paintings. We have videos too. We see in private home videos that Hitler playfully flirts, enjoys the company of children, and plays with his dog. Even individuals who are responsible for some of the worst atrocities in history have started out as seemingly normal individuals with joys, interests, and hobbies, just like anyone else. Villains are not simply born evil, but rather are shaped by a variety of factors, including past experiences, social conditioning, and personal choices.

Based on this, I wrote this writing exercise and posted it to my Instagram. It got more responses than usual, and so I thought it might be worth looking at a little deeper. (And yes, that castle painting is one of Hitler’s works of art.)

The question of how normal people can do evil things has puzzled psychologists and philosophers for decades. While it’s easy to understand why some individuals commit horrific acts due to a lack of empathy or sociopathy, it’s harder to comprehend how ordinary people can engage in cruel and immoral behavior.

One well-known psychological experiment that sheds light on this phenomenon is the Stanford Prison Experiment. In this study, participants were randomly assigned to be either guards or prisoners in a simulated prison environment. Despite being told that the experiment was only a simulation, the guards quickly began to engage in abusive and dehumanizing behavior towards the prisoners, while the prisoners became increasingly submissive and demoralized. The study was ended early due to the extreme and unethical behavior of the guards.

Another example of normal people doing evil things is the psychology of the SS in Nazi Germany. The SS was originally formed as a paramilitary organization to protect Adolf Hitler and other Nazi leaders. Over time, however, they became increasingly involved in the persecution and extermination of Jews and other minorities. Many members of the SS were not sociopathic; rather, they were ordinary men who had been indoctrinated into the ideology of the Nazi party and felt a sense of duty to follow orders. As part of their training, SS troopers were forced to raise and bond with a dog, only to have it taken away and killed in front of them. This was done to desensitize them to killing and to eliminate any empathy they might have felt towards their victims. The psychological abuse inflicted on the troops was a calculated effort to indoctrinate them into the Nazi ideology and turn them into ruthless killing machines.

Aside from the calculated traumas inflicted on SS recruits, another psychological explanation for their indoctrination is the idea of “groupthink.” When individuals are part of a group, they may feel pressure to conform to the beliefs and behaviors of that group in order to be accepted and valued. In the case of the SS, members may have felt that they needed to support the goals of the Nazi party in order to be seen as loyal and patriotic Germans. These young men thought of themselves as heroes—or at least dutiful patriots… and yet, we can see that they were quite the opposite.

Even when we do things incongruent with and against our own moral ideals, we tend to want to justify our own actions. But what sorts of things could cause us not to just live inconsistently with what we believe, but rather make us abandon those ideals wholesale? Casting oneself as a villain in a writing exercise can be a valuable exercise in self-reflection and exploration of one’s own psyche. It can be a way to delve into the darker aspects of our own personality and to better understand what motivates us.

To write a compelling villain, one must first consider the character’s backstory and what might have led them down a path of evil or villainy. This requires examining one’s own experiences and identifying potential sources of trauma or psychological distress that could lead someone to become a villain.

For example, a character who experienced a traumatic event in childhood, such as abuse or neglect, may develop a deep-seated distrust of others and a desire for power and control. Alternatively, a character who has experienced significant loss or betrayal may become consumed by anger and seek revenge against those they perceive as having wronged them.

By exploring these potential sources of trauma and psychology, writers can create complex and nuanced villains who are more than just caricatures of evil. This can also help individuals to better understand their own motivations and behaviors, and to identify areas for growth and self-improvement.

In addition, casting oneself as a villain can be a way to explore the idea of personal responsibility and agency. It can be easy to blame external factors for our own shortcomings or failures, but writing oneself as a villain forces us to confront our own actions and choices and to take ownership of them.

Overall, casting oneself as a villain in a writing exercise can be a challenging and rewarding exercise in self-exploration and creativity. It allows us to examine the darker aspects of our own psyche and to better understand what motivates us, while also creating complex and compelling characters that are more than just one-dimensional villains.

-

When Cultural Appropriation is Good for Civilization

Cultural appropriation has become a buzzword in recent years, with some claiming that it is a form of oppression that should be eliminated from society. Many people view cultural appropriation as a societal ill because it involves the adoption and exploitation of elements of a culture by members of a dominant culture without regard for the original culture’s values, traditions, and history. This can lead to the erasure or marginalization of the original culture, as well as the perpetuation of harmful stereotypes and tropes. However, cultural appropriation in certain forms has played a crucial role in the development of human societies and can be acknowledged as having positive effects rather than wholesale condemned.

To understand why cultural appropriation is a good thing, we can look back at some of the first great civilizations in human history. The Persians, Greeks, and Romans were notorious cultural appropriators, borrowing and adapting ideas and practices from the cultures they encountered through conquest or trade.

For example, the Persians adopted elements of Babylonian culture, such as their legal and administrative systems, while also incorporating aspects of Egyptian and Greek culture into their own. The Greeks were heavily influenced by the cultures of Egypt and Mesopotamia, while also incorporating ideas from the Persian and Indian cultures they encountered through their conquests.

The Romans, meanwhile, borrowed heavily from Greek culture, adopting their gods, art, philosophy, and even their alphabet. They also incorporated elements of Etruscan and Egyptian culture into their own, creating a unique blend of cultural influences that helped to shape the Western world as we know it today.

By borrowing from other cultures, these civilizations were able to expand their knowledge and understanding of the world, as well as develop new ideas and practices that contributed to the advancement of human society. The Greeks, for example, made significant contributions to philosophy, mathematics, and science, while the Romans developed a sophisticated legal system that formed the basis for modern Western law. These ideas, appropriated often by way of conquest demonstrates a rather nuanced view these imperial powers had over the cultures and civilizations they conquered—that there were things of value in a conquered people that could be incorporated into the empire for the benefit of all. Perhaps it’s rather unintuitive, but in some ways, ancient imperialism did have a penchant for a belief in the value of diversity.

Moreover, cultural appropriation helped to create cultural exchange and dialogue, leading to greater understanding and appreciation of different cultures. The Greeks, for example, were able to learn from the Egyptians and Mesopotamians about astronomy and medicine, while the Romans incorporated elements of the religions of the peoples they conquered, creating a rich tapestry of religious beliefs and practices.

Another example of cultural appropriation can be found in the Muslim world, where ideas of science and mathematics from ancient Greek culture were adopted and improved upon.

During the Islamic Golden Age, which lasted from the 8th to the 14th century, Muslim scholars made significant contributions to fields such as mathematics, astronomy, and medicine. However, much of their knowledge was based on the works of ancient Greek scholars such as Euclid, Pythagoras, and Aristotle. The Muslim scholars translated and studied these works, building on them and improving them through their own research and experimentation.

For example, the mathematician Al-Khwarizmi, who lived in what is now Uzbekistan, is credited with developing algebra as a discipline separate from arithmetic. He drew heavily on the works of Greek mathematicians such as Diophantus and Euclid, but also introduced new concepts and methods that transformed the study of mathematics.

Similarly, the Persian physician Avicenna drew on the works of Greek physicians such as Hippocrates and Galen, but also made significant contributions to the field of medicine through his own research and writing. His most famous work, the Canon of Medicine, was a comprehensive medical encyclopedia that remained a standard reference for centuries.

Through their cultural appropriation of Greek ideas, Muslim scholars were able to make significant contributions to the fields of science and mathematics, laying the groundwork for the scientific revolution of the Renaissance. Their work helped to advance human knowledge and understanding, and paved the way for modern science and medicine.

However, just like the Christian philosophers who would follow them in reading and interpreting the ancient Greeks, Muslims scientists did not ascribe any particular love or respect for other aspects of Greek culture—much of which is antithetical to tenets of Islam: its polytheism, sexual license, depictions of nudity, and general differences of philosophy. Like every cultural appropriator before them, they did not have a philosophy that all cultures were equal in value, but rather that most cultures had valuable aspects. One thing that we see in these early imperial powers is (at least generally) an attitude to incorporate other cultures into the empire, dispensing with certain practices that were considered irredeemable or wholly incompatible with the conquering culture. This created a cohesive state that could be governed and defended—and was more often than not far safer than a single smaller culture going it alone in a very violent antiquity.

In modern times, cultural appropriation continues to play a positive role in society, allowing for the exchange of ideas and practices that help to promote understanding and respect for different cultures. This is particularly true in the arts, where cultural exchange and collaboration have led to some of the most groundbreaking and innovative works of art in history.

Of course, there are legitimate concerns about cultural appropriation, particularly when it involves the exploitation of marginalized cultures or the misuse of cultural symbols and practices. However, I believe that these issues can be addressed through respectful engagement and dialogue, rather than through blanket condemnation of cultural appropriation as a whole. While we can certainly look to the history of cultural appropriation and see many sins and horrors committed by ancient imperial powers, we cannot be blinded by negativity bias and miss the astounding cultural advancements the sharing of ideas has had on humanity.

Cultural appropriation has been a driving force behind human progress and development, leading to greater understanding and exchange of ideas between different cultures. Rather than being wholly condemned as a form of oppression, cultural appropriation should be acknowledged as a positive force for human societies.

ancient empires, antiquity, art, bias, civilization, cognitive bias, colonialism, conquest, cultural appropriation, culture, diversity, empire, genocide, greece, greek, imperialism, iran, islamic golden age, melting pot, music, muslim culture, negativity bias, nuance, oppression, persia, persian, roman, rome, science -

Quinta Columna Calvinista #2: “I Saw Satan Laughing With Delight”

I woke up early the other morning as my son woke me and told me that he threw up. After doing the dad things, I found myself wide awake at 4:30am and started mindlessly cruising the reels on different social media platforms. One thing I noticed was such an overwhelming level of information—much of it conflicting. I wondered then, how in such a sea of information could one in search of truth in any matter find it? I remember life before the Internet, and while I had two sets of encyclopedias in my home, as well as countless books, most of my peers did not. What about before the printing press? Truth had to be a bit harder to find, perhaps? This led me on a bit of a theological rabbit hole as I considered the ever-shifting tactics of the enemy of truth, the old Deceiver himself: Satan.

Image of a riot or battle outside of a steepled church. In Christian theology, Satan is often portrayed as a malevolent being who seeks to undermine the work of God by perverting and corrupting what is good. This includes taking things that are meant to be blessings and turning them into sources of sin and destruction. One example of this is the way Satan twists the gift of sex for his own evil purposes. I recall as a high school student a pastor once describing sex as a wonderful thing that sex was a good gift from God meant to be enjoyed within the context of marriage between a husband and wife. But Satan seeks to pervert this divine gift in a number of ways. One way is through promiscuity, which is the practice of engaging in sexual activity outside of marriage. Another way Satan perverts the gift of sex is by stigmatizing it to the point where even married couples feel guilty or “dirty” for engaging in it. Satan is clever-enough to work in both extremes: license and legalism.

Though there are many in Christianity who may disagree, I think technological advancement is evidence of God’s common grace and benevolence on humanity. He’s granted mankind with curiosity and ingenuity in such a way that we seek to better our stations and so doing, reduce the miseries of a fallen creation on our fellow humans. But then, as with any good gift from God, the common grace of technology and human ingenuity can also be perverted and twisted by Satan. The printing press is a prime example of this. While it facilitated the Protestant Reformation and the widespread printing of the Bible, theological treatises, and other Christian literature, and countless other secular goods, it was also used to create propaganda, incite rebellions and mobs, and support cultural revolutions that sought to replace God and the Church with the sovereignty of the state.

Similarly, the Internet, which has the potential to facilitate the spread of the Gospel and promote truth (both religious and secular) on a global scale, is also prey to this Satanic tactic. The ease with which information can be shared online means that every foolish idea, deceit, propaganda, and obscenity imaginable is readily available to anyone with an Internet connection—and such things need not be sought after to be found. Satan uses the Internet to spread lies and deception, to undermine the truth of God’s Word, and to promote sin and evil. Pornography, which is easily accessible online, is a perversion of God’s good gift of human sexuality. The Internet is also used to promote false teachings, cults, and other forms of spiritual deception that can lead people away from the truth of the Gospel.

Moreover, the Internet has been used to create echo chambers, where people are only exposed to ideas and perspectives that confirm their own biases and prejudices. This can lead to a lack of critical thinking and an unwillingness to engage with opposing viewpoints, which can ultimately lead to division and conflict.

As Christians, we need to be aware of Satan’s tactics and be discerning in our use of technology and the Internet. We need to guard our hearts and minds against the lies and deceptions that are so readily available online, and we need to be intentional about seeking out and promoting truth, goodness, and beauty in all areas of life. At the same time, we must also use technology and the Internet to advance the cause of the Gospel, sharing the truth of God’s Word and promoting justice, mercy, and compassion in a world that desperately needs it. I think there is an idea that we should take after the Amish when seeing how twisted some technology can become—that we can as Christians somehow say with validity “stop the world! I want to get off!” But I don’t think this is the case. The world, humanity, truth, and all things belong under the dominion of the One True and Living God. Invention and other products of human endeavor are not to be fled because there are evils in them that reflect our own sinful natures, but rather like our natural selves, our products should be consecrated to God—just as the produce of agriculture and shepherding once was commanded in Scripture.

-

An excerpt from the my work-in-progress on Teaching Writing with ChatGPT:

The development of ChatGPT marks a significant milestone in the history of information and communication technologies. Much like the invention of the printing press revolutionized the dissemination of knowledge and information in the 15th century, ChatGPT represents a new frontier in the field of natural language processing. Just as the typewriter and word processor transformed the way in which written documents were produced and edited, ChatGPT has the potential to revolutionize the way we interact with computers and access information. ChatGPT, with its ability to generate human-like responses to text input, has the potential to transform the way we communicate and collaborate, much like these previous technological advancements.

ChatGPT can be useful for a variety of writing-based tasks, including:

- Content Generation: it can generate coherent and coherently written articles, stories, summaries, and more on a wide range of topics.

- Text Completion: it can complete partially written sentences, paragraphs, and even entire articles.

- Summarization: it can generate concise summaries of long documents or articles, helping to condense information into more manageable chunks.

- Question Answering: it can respond to questions by generating relevant and informative answers.

- Translation: it can translate text from one language to another, making it a useful tool for multilingual writing tasks.

- Proofreading and Editing: it can identify and suggest corrections for spelling, grammar, and punctuation errors in written text.

In general, ChatGPT is a powerful tool for automating and improving various aspects of writing, making it a valuable asset for individuals and organizations that rely on written communication.

Challenges in the English Classroom

AI tools, like the impressive ChatGPT, have the potential to significantly impact the field of education, including the teaching of English. However, they also present new challenges that English teachers must address. One of these challenges is academic dishonesty, including plagiarism.

Using these tools, students now have access to an unlimited source of information and can generate high-quality written content with ease. This has the potential to make academic dishonesty even more prevalent than tools like Google already made it—and also much more challenging to catch (and prove).

Another challenge posed by AI tools like ChatGPT is the potential for students to rely too heavily on these tools for their writing assignments. While AI tools can be useful for generating ideas and providing support, students must still develop their own writing skills and critical thinking abilities. Teachers must educate students on responsible use of AI tools and emphasize the importance of developing their own writing skills.

AI tools also raise questions about the role of the teacher in the classroom. While these tools have the potential to make the teaching process more efficient, they also raise concerns about job loss and the future of teaching. Teachers must continue to demonstrate their value and importance in the classroom, by providing personalized attention, guidance, and support to their students.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.